"I have such perfect vineyards now. I bought them for the next generation."

Saturday, September 22, 2012

long-term thinking

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

heart of rice

the acetarium is currently more than usually overstocked with obscure sakes, having recently received a few especially abstruse bottles from their japanese correspondents in their regular shipment of ceramics, edibles, and potables. they pulled these two bottles out at dinner last week.

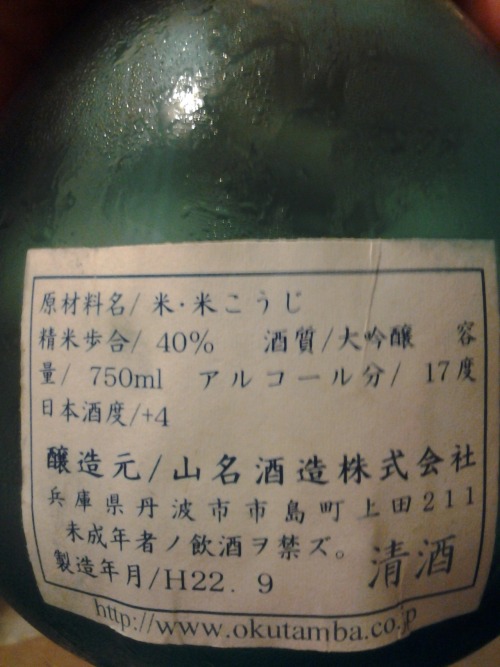

okutamba's yamana brewing company maintains a subscription service for sake nerds interested in exquisite, small-run bottlings—including this bulbous blue bottle containing a light, aromatic alcohol-added daiginjo that was limpid and more water-like than water (the 17% alcohol was not noticeable). 60% of the rice grain was milled away before brewing, removing bran, aleurone layer, germ and leaving only the fermentable starch core. the bouquet implications might be inferred from the difference in the aromas of cooked unmilled (brown) and milled (white) aromatic rice: the former earthy, nutty, slightly vibrating, the latter floral, quiet, pure, and calm. as in natural wines, these more delicate aromas are further enhanced by slow fermentation with native yeast populations at low temperatures. the scent of steaming white rice is distinct, round, generous, never overwhelming. this sake expresses this quiet kitchen pleasure.

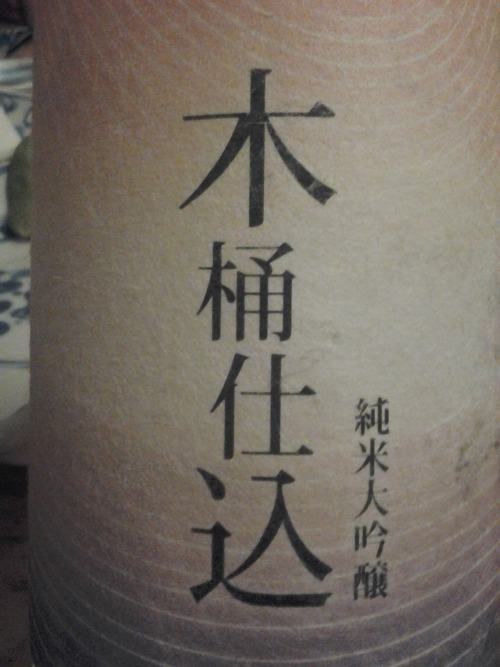

the second bottle is an twenty-year aged pure rice daiginjo from the imayotsukasa brewing company in niigata, made with sake rice grown in niigata and sold only at the brewery in limited quantities. the kanji on the front label suggests that wood vats were used in production but this sake, though an unusual pale gold colour, was not woody or resinous in the least. neither the label nor the company's surprisingly comprehensive website are of any help in figuring out how the stuff was made. drinking this sake was like eating a bowl of great rice: richly flavoured, light but full-bodied with delicate texture and a slight chewiness, good just a little colder than room temperature, possibly even better slightly warm. the benefits of heterodoxy are numerous.

clearly, another stopover in japan is necessary.

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

be here now

midway through the first annual nordic food symposium, the kitchen sent out two large bowls of tiny, ripe june-bearing strawberries scattered with anise-scented wild herbs, with cream from pastured danish cows. this is the best new nordic cuisine—perfect products, simply prepared. such rigorous and complex simplicity, done well, conceals the experience and maturity necessary to produce it. choosing food at the height of its flavour takes knowledge and experience; serving that food simply prepared and mostly unadorned takes confidence and self-knowledge.

simple food conceals its complexity. take, for instance, the foraged wild plants that now show up everywhere, especially in the nordic countries. thorsten schmidt, host of the symposium and chef behind malling and schmidt, showed us a few of the fields and forests from which he gathers wild vegetables and herbs for his restaurant in aarhus. learning about the culinary uses of these plants has been a multi-year exercise in trial and error, schmidt said. "i wanted to use more of the plants that grow in jylland than the farmers grew at the time but we had no local foragers to gather them for us. i had to learn how to identify and use these plants myself ... it was slow to start with,” he says, “but i now use more than 180 plants from around here to accent my cooking.”

he discovered early on that botanical field guides are useful for survival but not gastronomy. they often indicate if a plant is edible but almost never explain how plants might be used by cooks interested in their flavour or texture. they also rarely describe how plants look like as they grow through the year. over the last few years, schmidt has developed a network of experts who help him discover the wild foods around aarhus. one of these is a botanist with a particular interest in edible plants. "i send him a photograph of the plant,” schmidt says, “and he tells me how much i would have to eat for it to be poisonous. then i start experimenting with it, picking, tasting, and cooking with different parts of the plant every few weeks."

a slow, trial-based, experimental approach like this is critical because knowing what to eat is mostly about knowing when and how to eat a particular food. this is especially true when the seasons are as dramatic and change as quickly as they do this close to the arctic circle.

bo bech, from geist in copenhagen, was also at the symposium. the dish he made for dinner on the second night featured grilled baby leeks. "we forget that things change through their lives," he explained. "no one in denmark, maybe no one anywhere, harvests baby leeks this small. these are just a few days old and they will surprise you." he handed me a baby leek to illustrate. it was an unpromising vegetable, looking like a cross between a weedy tuft of grass and and a very slender scallion. but grilled for just a few minutes on one side over a very hot fire, the leeks became soft, sweet, and juicy on the charred side, pungent with the green flavours of garlic and white onions on the raw side.

grilling a baby leek on only one side is about cooking in the moment: a leek is young enough to be cooked like this for only a few days in its growing cycle. after that it is a regular leek, too big and fibrous to eat without long, slow, moist heat. cooking in the moment means learning not only that a leek is good to eat for this vanishingly small window of its life, but also that it is delicious cooked in a way totally different from how leeks are usually cooked.

warmed smoked eel, crème fraîche, char-grilled baby leeks, raw nasturtium leaves, carbonized garlic, by bo bech. (photo by claes bech-poulsen.)

"something we have had to do is learn how to use the products as they change through the seasons, to appreciate something for what it is right now instead of wishing it was something else, to be willing to reorganize the menu completely when a particular ingredient suddenly goes out of season because of the weather," schmidt says. "it takes a bit of rethinking on the part of the chef and diner. we have to learn to eat things as they are and figure out how to make them the best for what they are instead of wanting something that is out of season."

committing to cooking in the moment, especially when the moments are as fleeting as they can be in the nordic region, requires that the chef gives up the predictability that buying produce from all over the world offers.

schmidt says that "it takes a while to learn to subdue your ego and get used to not just letting yourself take the easy way out and ordering whatever your purveyors have, whether or not they're in season. you learn to cook whatever is available. when you're lucky enough to have beautiful ingredients, your responsibility is to do the work to find out what they are, when to use them, and how to cook them as simply as possible." in exchange, the chef grows comfortable with responding in the moment and eventually develops the knowledge and confidence to seek out the best products and then serve things at the peak of their ripeness almost completely unadorned, as schmidt did: perfect, perfumed strawberries accompanied by nothing more (and nothing less) than a shower of herbs and pale gold cream smelling of fresh-cut grass.

simple food conceals its complexity. take, for instance, the foraged wild plants that now show up everywhere, especially in the nordic countries. thorsten schmidt, host of the symposium and chef behind malling and schmidt, showed us a few of the fields and forests from which he gathers wild vegetables and herbs for his restaurant in aarhus. learning about the culinary uses of these plants has been a multi-year exercise in trial and error, schmidt said. "i wanted to use more of the plants that grow in jylland than the farmers grew at the time but we had no local foragers to gather them for us. i had to learn how to identify and use these plants myself ... it was slow to start with,” he says, “but i now use more than 180 plants from around here to accent my cooking.”

he discovered early on that botanical field guides are useful for survival but not gastronomy. they often indicate if a plant is edible but almost never explain how plants might be used by cooks interested in their flavour or texture. they also rarely describe how plants look like as they grow through the year. over the last few years, schmidt has developed a network of experts who help him discover the wild foods around aarhus. one of these is a botanist with a particular interest in edible plants. "i send him a photograph of the plant,” schmidt says, “and he tells me how much i would have to eat for it to be poisonous. then i start experimenting with it, picking, tasting, and cooking with different parts of the plant every few weeks."

a slow, trial-based, experimental approach like this is critical because knowing what to eat is mostly about knowing when and how to eat a particular food. this is especially true when the seasons are as dramatic and change as quickly as they do this close to the arctic circle.

bo bech, from geist in copenhagen, was also at the symposium. the dish he made for dinner on the second night featured grilled baby leeks. "we forget that things change through their lives," he explained. "no one in denmark, maybe no one anywhere, harvests baby leeks this small. these are just a few days old and they will surprise you." he handed me a baby leek to illustrate. it was an unpromising vegetable, looking like a cross between a weedy tuft of grass and and a very slender scallion. but grilled for just a few minutes on one side over a very hot fire, the leeks became soft, sweet, and juicy on the charred side, pungent with the green flavours of garlic and white onions on the raw side.

grilling a baby leek on only one side is about cooking in the moment: a leek is young enough to be cooked like this for only a few days in its growing cycle. after that it is a regular leek, too big and fibrous to eat without long, slow, moist heat. cooking in the moment means learning not only that a leek is good to eat for this vanishingly small window of its life, but also that it is delicious cooked in a way totally different from how leeks are usually cooked.

warmed smoked eel, crème fraîche, char-grilled baby leeks, raw nasturtium leaves, carbonized garlic, by bo bech. (photo by claes bech-poulsen.)

"something we have had to do is learn how to use the products as they change through the seasons, to appreciate something for what it is right now instead of wishing it was something else, to be willing to reorganize the menu completely when a particular ingredient suddenly goes out of season because of the weather," schmidt says. "it takes a bit of rethinking on the part of the chef and diner. we have to learn to eat things as they are and figure out how to make them the best for what they are instead of wanting something that is out of season."

committing to cooking in the moment, especially when the moments are as fleeting as they can be in the nordic region, requires that the chef gives up the predictability that buying produce from all over the world offers.

schmidt says that "it takes a while to learn to subdue your ego and get used to not just letting yourself take the easy way out and ordering whatever your purveyors have, whether or not they're in season. you learn to cook whatever is available. when you're lucky enough to have beautiful ingredients, your responsibility is to do the work to find out what they are, when to use them, and how to cook them as simply as possible." in exchange, the chef grows comfortable with responding in the moment and eventually develops the knowledge and confidence to seek out the best products and then serve things at the peak of their ripeness almost completely unadorned, as schmidt did: perfect, perfumed strawberries accompanied by nothing more (and nothing less) than a shower of herbs and pale gold cream smelling of fresh-cut grass.

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

mindful eating

Eating is often a knee-jerk reaction: we cook and eat what is most convenient, what is least expensive, what appears to taste good. But deciding what to eat involves consequences that are wide-ranging and long-lasting, even if we don't recognise what those consequences are. We can only make good decisions about what actions to take by knowing the consequences of those actions. And we can only know these consequences if we investigate, inquire, and gather more information.

Meat is a good example. Meat is environmentally costly. Most easily available meat is intensively raised and processed in operations that raise ethical and food-safety concerns in addition to the environmental ones. Learning more about meat production allows you to make better decisions about the meat you choose to consume. You may choose to eat less meat, and buy what meat you do eat from producers who claim to raise and process the meat in ways that minimise the risk of food-borne illness. In doing so, you are choosing to eat not the least expensive or most convenient meat, but rather the meat that is produced with attention to health or environmental impact. Or you may continue eating the meat you've always eaten, with a better knowledge of the risks that you are exposed to.

Another example: You go to eat at a very good restaurant. The food has been made with care from good ingredients. The check comes—it is for a staggering amount. Yet the prices, though high, are subsidised by chefs, stagiers, and producers who work long hours for little money; there is not much profit in food sourced and made with care. Fast food, in contrast, is inexpensive. It is often indifferently made with indifferent ingredients. There is much profit in fast food. Questioning what goes into the price of the food you eat may make you decide to cook for yourself most of the time and to eat out infrequently and only at restaurants that cook with care. Or it may not.

All this has been said before. Being mindful of the consequences of eating sounds like submitting to nothing but limitation, restrictions, and unaffordable food. Acknowledging, for instance, that eating food grown far away seriously damages the environment means for the most part restricting the food you eat to things that can be more efficiently grown locally than elsewhere—invariably a smaller and less predictable selection.

But the limitations imposed by mindful eating are not the full story.

Questioning what, how, and why we eat limits us in some ways but also opens up new possibilities. Limitations are like frames that, by excluding much of the view, allow you to look more closely at whatever is within the frames. If you decide to eat only local, seasonal fruit, you have no choice but to begin to pay close attention to the fruit that is around you. But you come to realise that strawberries taste different from day to day as the season progresses, that there are in fact different varieties of strawberries that ripen at different times, and you begin to eat strawberries only when they are at their very best.

Asking questions about the food you eat can lead you to discover techniques and methods of cooking and flavour combinations that are new to you but well-known elsewhere and to other people. For cooks, asking questions and finding answers is a way to learn how to express a particular sense of what tastes good and what is good to eat. It is also a way to develop that particular sense, the style of cooking that distinguishes you from other chefs: a way to develop a vocabulary for communicating your values in food, the reason why you cook.

We should ask ourselves a multitude of questions about the food we eat. Our decisions about food will be informed by the answers we find. The point is not to find the single right answer to each question—it doesn't exist—but rather to begin to ask the questions.

Meat is a good example. Meat is environmentally costly. Most easily available meat is intensively raised and processed in operations that raise ethical and food-safety concerns in addition to the environmental ones. Learning more about meat production allows you to make better decisions about the meat you choose to consume. You may choose to eat less meat, and buy what meat you do eat from producers who claim to raise and process the meat in ways that minimise the risk of food-borne illness. In doing so, you are choosing to eat not the least expensive or most convenient meat, but rather the meat that is produced with attention to health or environmental impact. Or you may continue eating the meat you've always eaten, with a better knowledge of the risks that you are exposed to.

Another example: You go to eat at a very good restaurant. The food has been made with care from good ingredients. The check comes—it is for a staggering amount. Yet the prices, though high, are subsidised by chefs, stagiers, and producers who work long hours for little money; there is not much profit in food sourced and made with care. Fast food, in contrast, is inexpensive. It is often indifferently made with indifferent ingredients. There is much profit in fast food. Questioning what goes into the price of the food you eat may make you decide to cook for yourself most of the time and to eat out infrequently and only at restaurants that cook with care. Or it may not.

All this has been said before. Being mindful of the consequences of eating sounds like submitting to nothing but limitation, restrictions, and unaffordable food. Acknowledging, for instance, that eating food grown far away seriously damages the environment means for the most part restricting the food you eat to things that can be more efficiently grown locally than elsewhere—invariably a smaller and less predictable selection.

But the limitations imposed by mindful eating are not the full story.

Questioning what, how, and why we eat limits us in some ways but also opens up new possibilities. Limitations are like frames that, by excluding much of the view, allow you to look more closely at whatever is within the frames. If you decide to eat only local, seasonal fruit, you have no choice but to begin to pay close attention to the fruit that is around you. But you come to realise that strawberries taste different from day to day as the season progresses, that there are in fact different varieties of strawberries that ripen at different times, and you begin to eat strawberries only when they are at their very best.

Asking questions about the food you eat can lead you to discover techniques and methods of cooking and flavour combinations that are new to you but well-known elsewhere and to other people. For cooks, asking questions and finding answers is a way to learn how to express a particular sense of what tastes good and what is good to eat. It is also a way to develop that particular sense, the style of cooking that distinguishes you from other chefs: a way to develop a vocabulary for communicating your values in food, the reason why you cook.

We should ask ourselves a multitude of questions about the food we eat. Our decisions about food will be informed by the answers we find. The point is not to find the single right answer to each question—it doesn't exist—but rather to begin to ask the questions.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

revelations of unexpected balance

it isn't every friday night that i have more drinks than i can count. but if certain people—"the priests" roger scruton believes "that Bacchus has spread around our world, and who pursue their calling in places which can be discovered by accident but seldom by design"—are drinking with me, all bets are off.

heath hutto blows through town on occasion, each time stopping at drink on the way from logan (a 7-minute cab ride). though he now lives in a truly american state, he is known to the house and is probably there more often than i am. i left my beverage selections to him and will thompson behind the bar. they jointly settled on a series of what will called "revelations of unexpected balance."

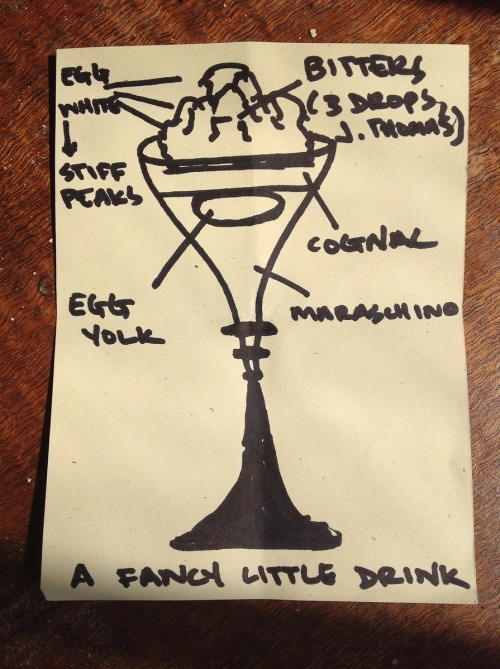

the dead man's mule (ginger beer, muddled lime, orgeat, allspice dram, and absinthe) is a superb balance of spice, heat, anise, and the bittersweet fragrance of almonds; it changed my mind about anise in drinks. chewy, bitter, creamy, aromatic, the trinidad sour is made with equal parts angostura and orgeat, shaken with the softening influences of lemon and rye. leo engel's knickebein—an involved drink (see will's diagram above) featuring a whole raw egg yolk, whipped egg whites, a bit too much maraschino, and some theater in production and consumption—would have been improved by removing the chalazae on the end of the yolk (for this task, a pair of little scissors is handy). the little valiant (salers, cocchi americano, lemon, angostura, Big Ice, salt) is a variant on the little giuseppe (punt e mes, cynar, etc); both play salt against bitter and the two pale gentians in the little valiant were a winning combination that also looks much nicer in the glass. at the end, heath asked for three glasses of schuylkill fish house punch ("why three?" "one for you, two for me." "ah.") which the bar prepared in over-generous quantity and served up in a gallon punchbowl. the formula calls for cognac, lemon, sugar, rum (2 quarts), and peach brandy. apricot brandy substituted for the peach, this last being unavailable. after some of the ice had melted, it was a bracing and correct way to end a night filled with highly alcoholic and unconventional drinks.

among the many benefits of strictly limiting yourself to quality beverages made with careful attention to detail is the sensation of waking the morning after consuming at least twelve (but more probably fourteen) drinks with a feeling of profound freshness and clarity.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)